It’s 1983. I’m sitting behind our apartment in Tucson, the desert sunlight dappling down through pomegranates, creosote, and a grapefruit tree, doing homework from my University of Arizona post-bachelor’s teacher prep program. I’m 25 years old.

My husband joins me and says, “I’m thinking about starting the ordination process.”

“Oh. Okay,” I say. I remember feeling excited about a new adventure, and happy to go along for the ride.

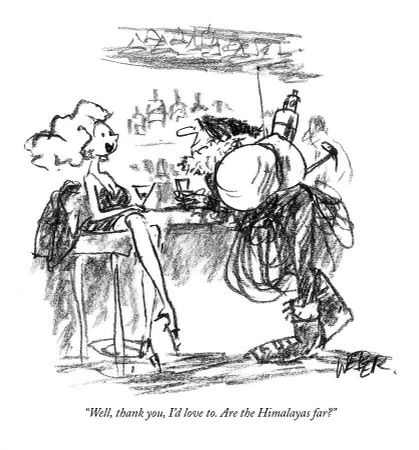

“Well, thank you, I’d love to. Are the Himalayas far?”

Jed’s vocation has taken me places I never would have landed otherwise. Four years of seminary. Two babies. Six cities and five states—Massachusetts, New Mexico, Missouri, Illinois, and Oregon. Twelve houses. Nine jobs (for me).

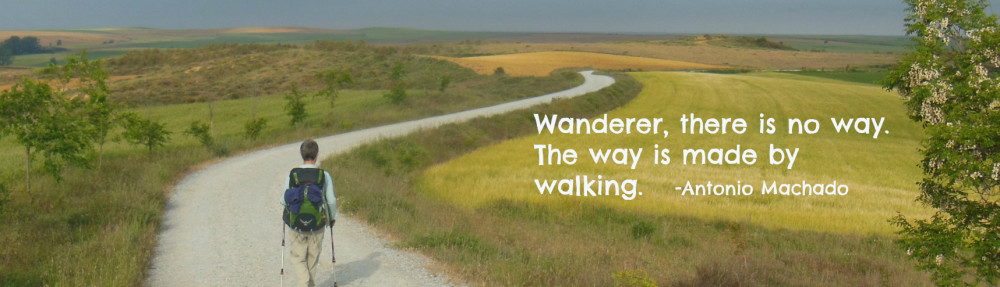

I have friends all over the US, and a few in Europe. I’ve had a unique perspective on Church in action, both good and bad. I’ve enjoyed the benefits of Jed’s sabbaticals: England and Ireland, Iona, the Camino de Santiago.

This life has also been costly. 25-year-old Barb had no idea what she was saying yes to.

I’ve been doing this clergy spouse thing in one form or another for forty years, since the day Jed told me he wanted to pursue ordination as an Episcopal priest.

“Well, thank you, I’d love to. Are the Himalayas far?”

Jed recently announced that he’s retiring this summer. (Trinity, Bend readers: You’re awesome! I love you so much.)

We’ve been anticipating his retirement for years, imagining what it might be like and what we might do.

But now that it’s here, I’m noticing a part of me hanging on for dear life, resisting the upcoming seismic shift. As costly, painful, crazy-making, and occasionally lonely as these decades have been, this is the life and the marriage I know. This is the life I’ve conformed myself around. This is the life I’ve cut off pieces of myself to fit into.

Two primary threads weave this web of resistance, I think: my relationship to change, and the difference between soul and façade.

First, change.

We’ve all been doing this change thing since puberty, really. Followed by leaving home for the first time. Graduating from college. Committing to a life partner, and maybe deciding to become parents. These celebratory changes in the first half of life are then followed by a smorgasbord of the more complicated changes: Divorces. Serious Illness. Retirements. Big moves. Deaths.

Just because we’ve been doing the “Change Cha-Cha” for our entire lives doesn’t mean we know how to do it well.

Marriages, births, divorces, deaths, retirements, serious illnesses, big moves—they’re all Square One dissolution events.

Wayfinder Life Coaches learn this mantra for Square One: “I don’t know what the hell is going to happen … and that’s okay.” I’m changing this to: “I don’t know what the hell is going to happen … and I’m okay.”

To complicate matters, Jed and I have also got our feet in Square Two, as we begin to imagine concretely what these actual bodies of ours will do beginning in August. The Square Two mantra? “There are no rules … and that’s okay.” Modifying again: “There are no rules … and I’m okay.”

I’m also grappling with the loss that accompanies change. We’ll be leaving a community that is dear to us. Places that are dear to us. And people that are dear to us.

Underneath those obvious losses is a more subtle, sneaky thing poking my heart. I can’t tend to this sneaky thing until I see it. And to see it, I’ve had to sit still for a long time, look within, and listen to myself.

Which brings me to Soul and Façade:

That part of me that’s hanging on, asking for attention and poking me until I listen? It’s that social self I’ve constructed over more than six decades, buttressed by being “the rector’s wife” for so many years. It’s my façade, feeling itself in danger, clinging desperately for survival.

Social Self, False Self, Ego, Façade, Cultural Self—all are labels for the same necessary part of ourselves: the part we show to the world in order to get through our days. This façade, first formed in infancy and childhood, is continually refined throughout our first four or five decades. Finally, hopefully, we begin to let go of that false front in midlife, when it gets too damn heavy to carry around. If we do the work.

For so many years, it was just easier to be who I was expected to be than to seek for the pure strength of my Soul within me. And, of course, as kids we don’t have the option to say, “Screw you and your bullshit cultural rules. I’m gonna be ME!” We must figure out what behaviors will keep us alive, and those behaviors get wired in.

For the first time in our adult lives, Jed and I can let those roles drop away. We can be whoever we want to be, individually and together. Oh, the freedom of that! And the anxiety. We’re a little “deer in the headlights” right now. When those roles drop away, we’ll be vulnerable and naked. And new.

Who will I be?

Who will he be?

Who will we be?

“Well, thank you, I’d love to. Are the Himalayas far?”

Here’s what’s helping me to stay over my feet right now, this minute:

1. I’m remembering that the Change Cycle is baked into our Earthling DNA. Death and rebirth, over and over and over, is what life on Earth is all about. Even rocks get into it. Resistance is futile. I have the tools to ride this wheel. I have understanding. I have my mantras. I’m okay.

2. I’m intentionally discerning who’s speaking, who’s running the show. Is it my Social Self/False Self/Façade? Or is it my Soul? The façade part of me is scared shitless, really worried about doing this right, and bracing herself against all the impending loss. My Soul, however, when I get down to her, is peaceful, connected, and not the least bit worried. So I’m spending a lot of time being quiet and listening.

3. I’m paying attention to what feels good in my body. My body came into this world knowing what’s true for me. She still does. I simply need to use my skills, pay attention, and trust her guidance. Staying present and connected feels good. Worrying does not.

(These skills—Embodiment, Soul-based Living, and Skillful Change—are components of my Coaching Intensive program.)

What does this mean for my coaching practice? I feel comfortable committing to this work through June. After that, who knows? Not me. So if you’re feeling the nudge for private coaching, now is the time to connect for a Clarity Call.

I’m also creating a three-month Group Coaching Intensive to begin in March. Details to come! If you’d like more information about that, let me know.

Ooof! This is a long one. Thank you for hanging in with me!

Gratefully yours,

Barb

P.S. This is the blog version of my weekly-ish newsletter. That’s where I share my latest writing, news, and coaching offerings. You can subscribe here, and thank you!

Image: New Yorker cartoon, by Robert Weber